The belief that a stone in the skull caused an imbalance of the soul began in the Late Middle Ages and continued until the Renaissance, and was held above all in Northern Europe.

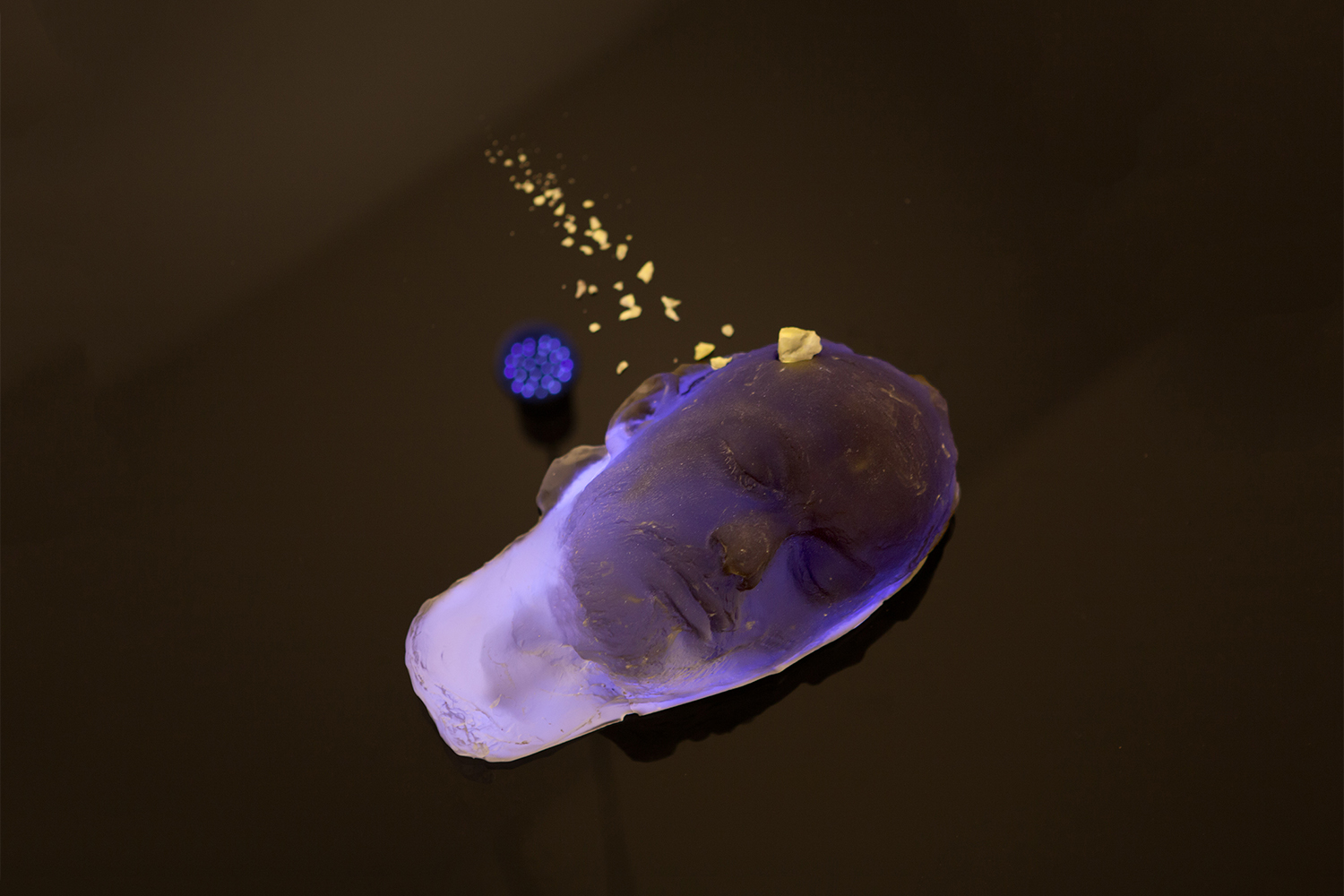

According to popular superstitions this little rock, which for unknown reasons appeared inside the head of some individuals, caused behavioural deviance, madness, and strangeness. It was considered to be a foreign body, which had to be removed. This ‘extraction’ process, a practice that pre-dated modern surgery, was represented in paintings, engravings, and literary texts until it fell into the category of those strange practices and beliefs that history has isolated and forgotten.

In any case, cranial trephination was not a medieval invention: Hippocrates wrote about it and archaeology has documented testimonies dating back 8,000 years. Prehistoric people performed operations on the skull using a flint scraper and in various parts of the planet, the practice survives today as a propitiatory rite, or more generally as a method that allows the spirits – whether good or evil– to exit the body and mind.

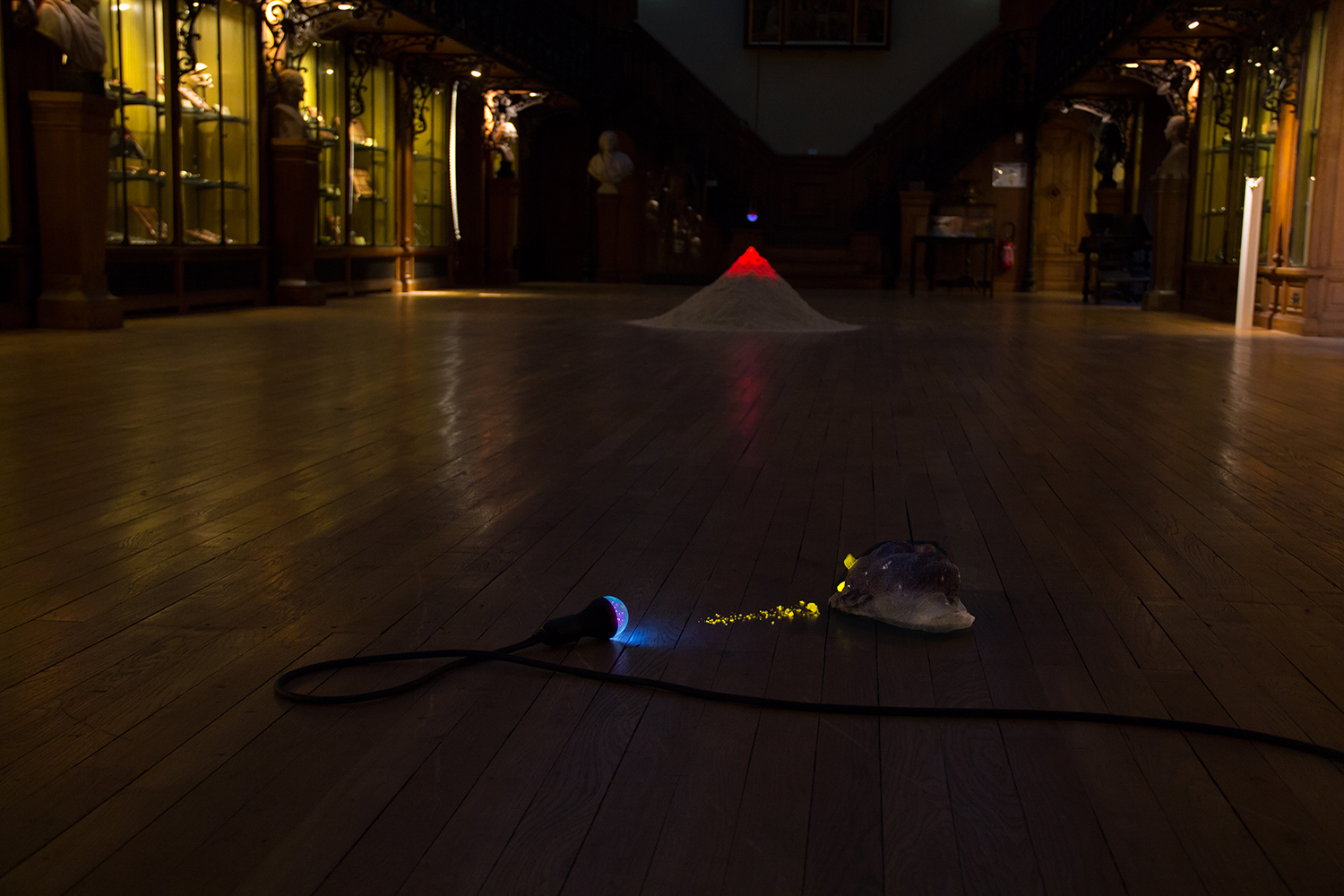

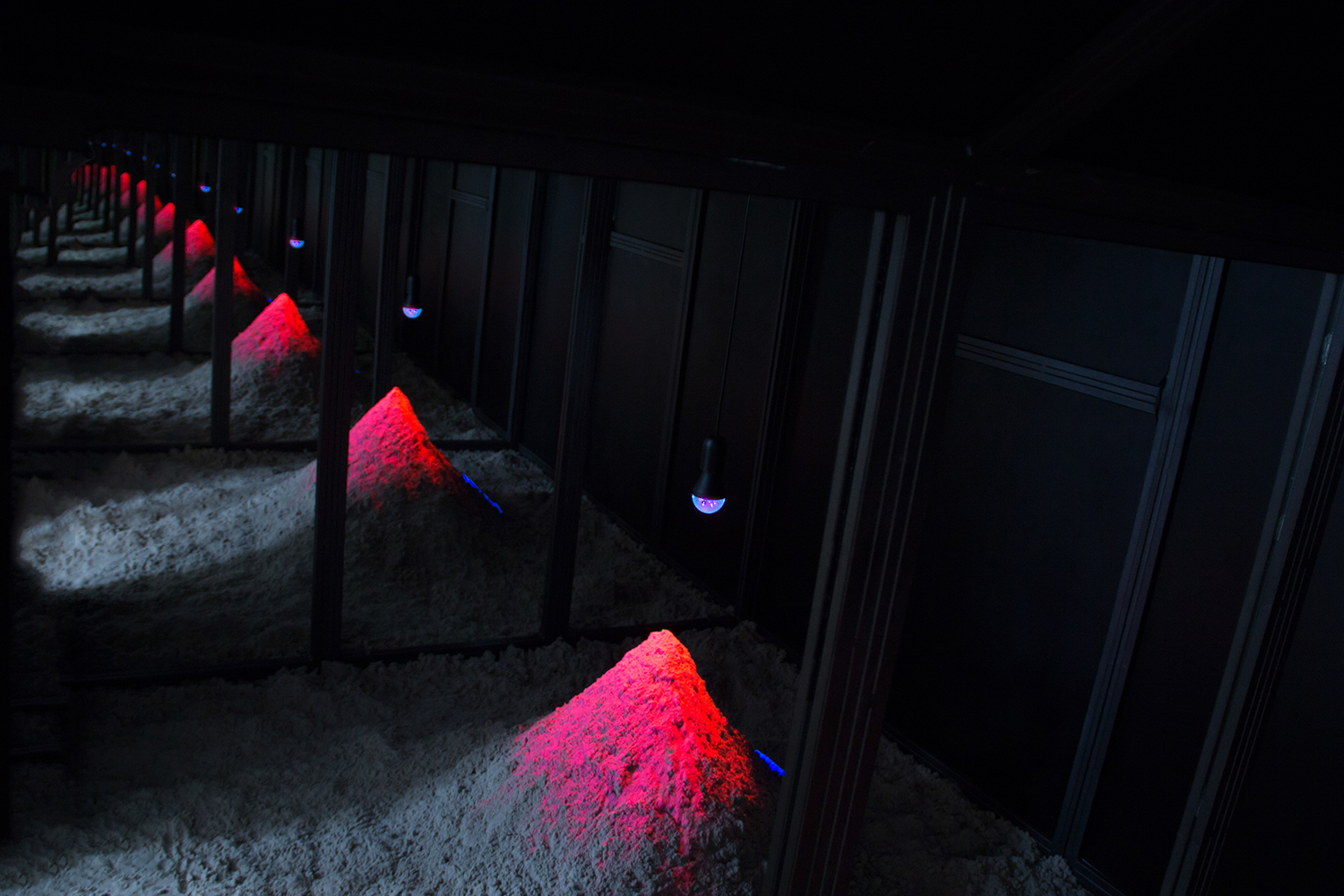

The Stone of Madness project, begun in 2017, proposed the investigation of factors linked to these traditions and beliefs based on testimonies that have been passed down and are still kept in museums or their archives today.

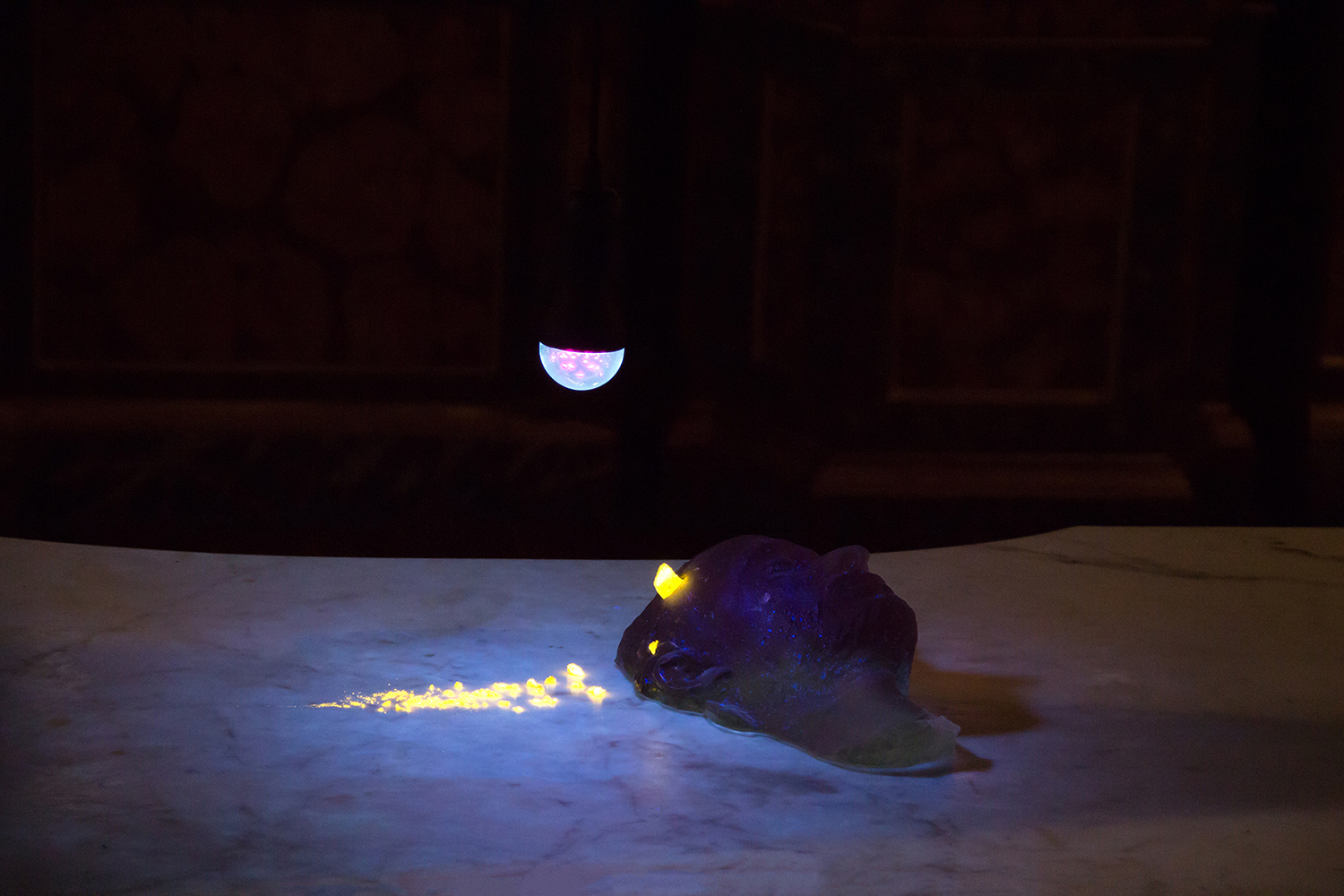

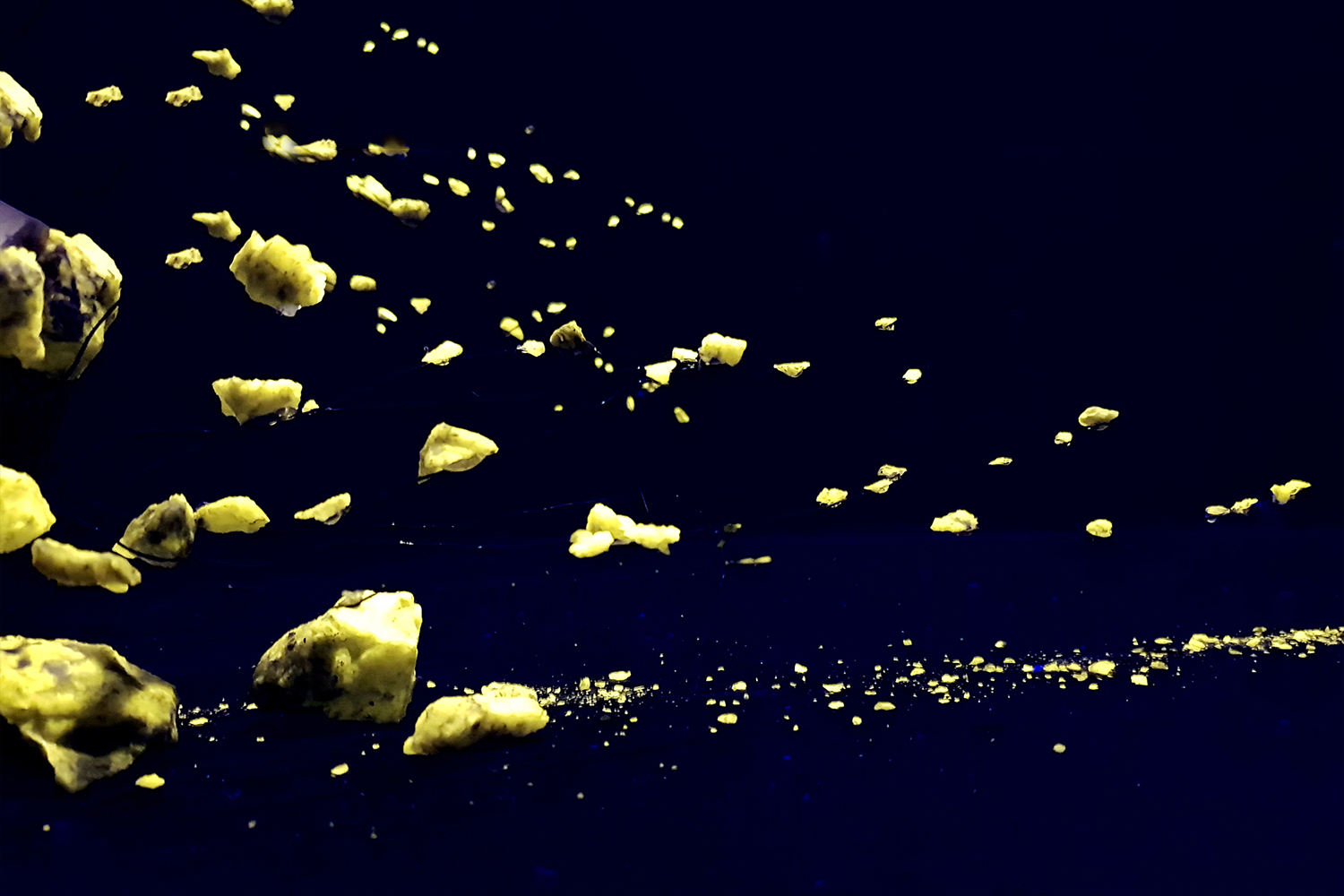

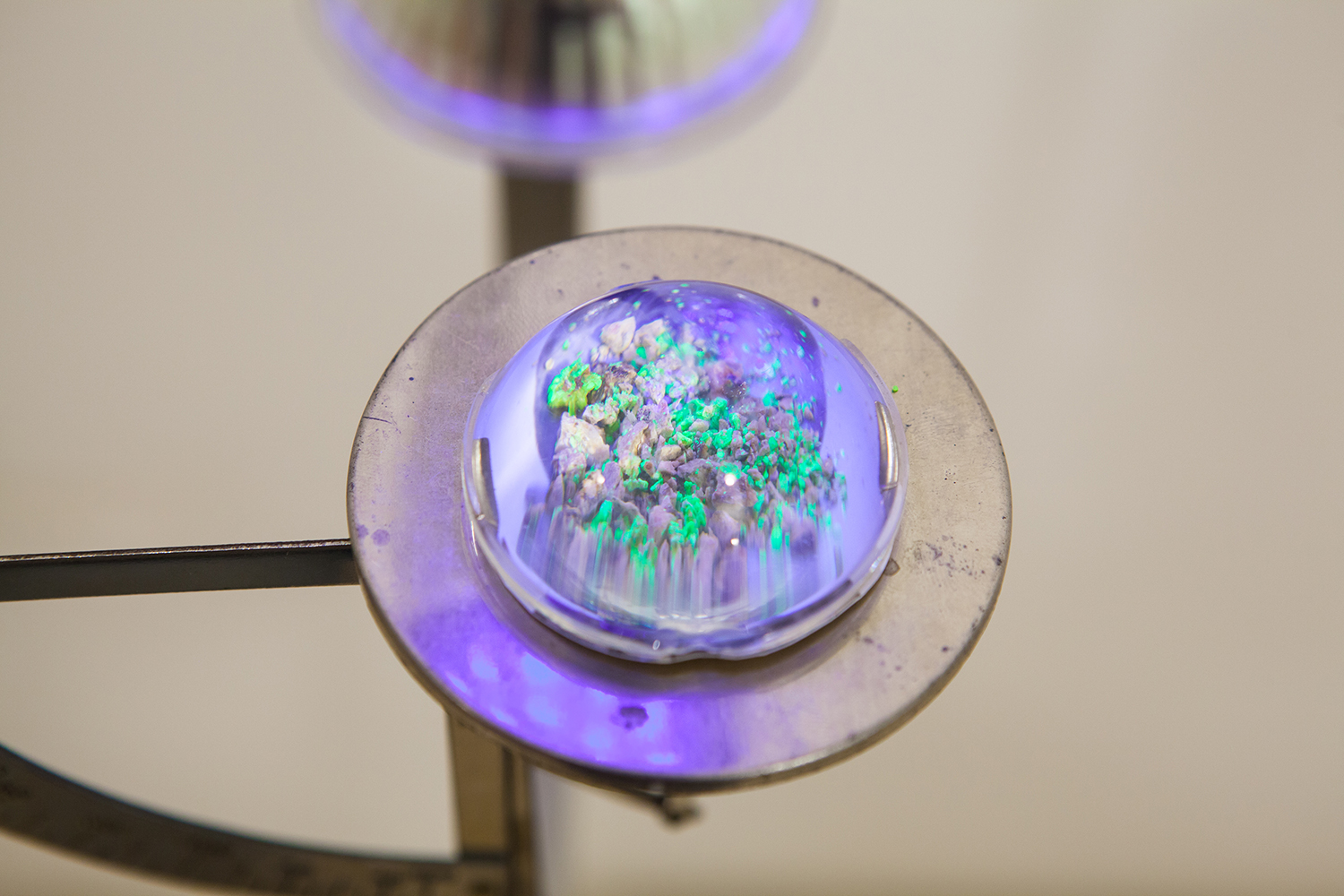

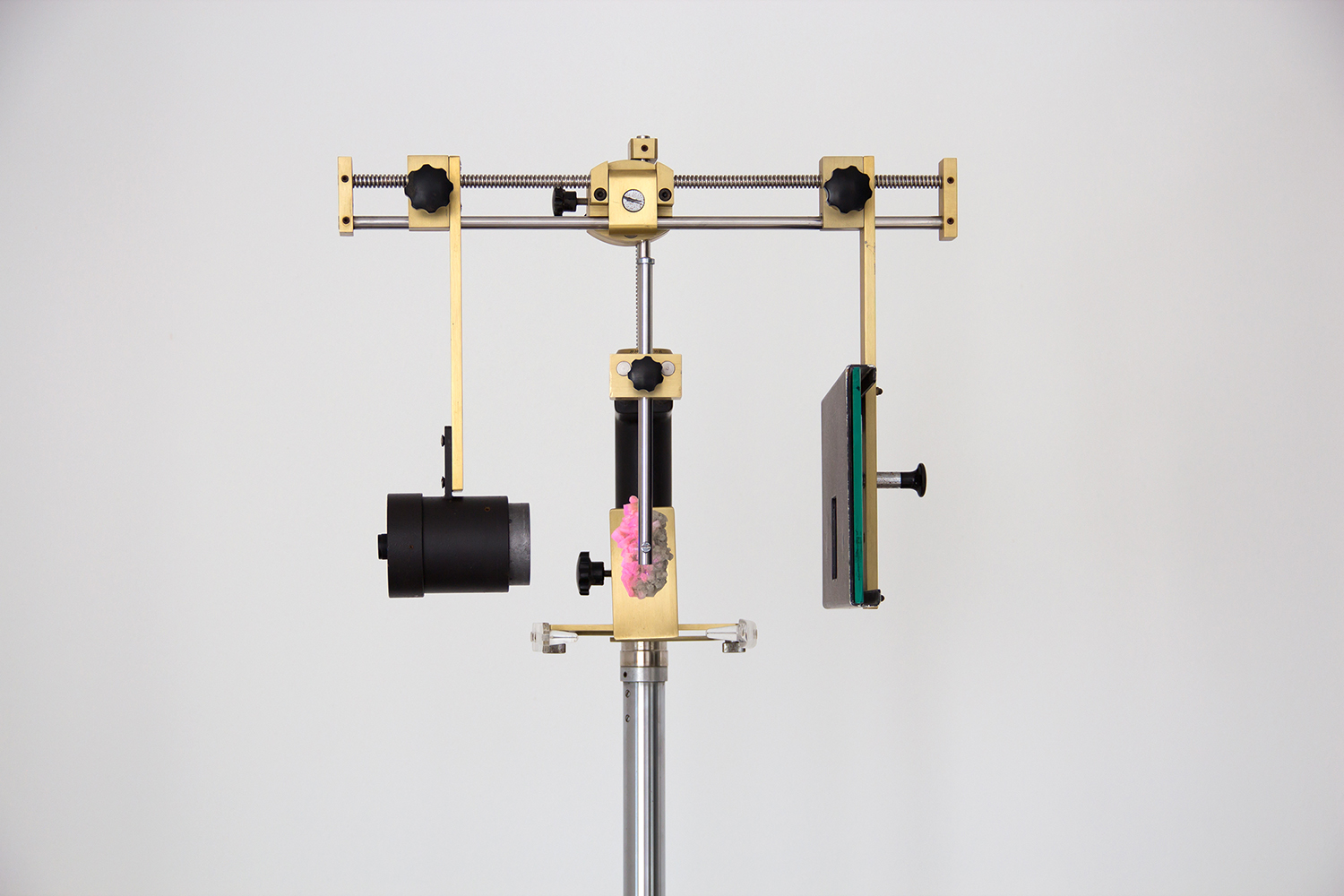

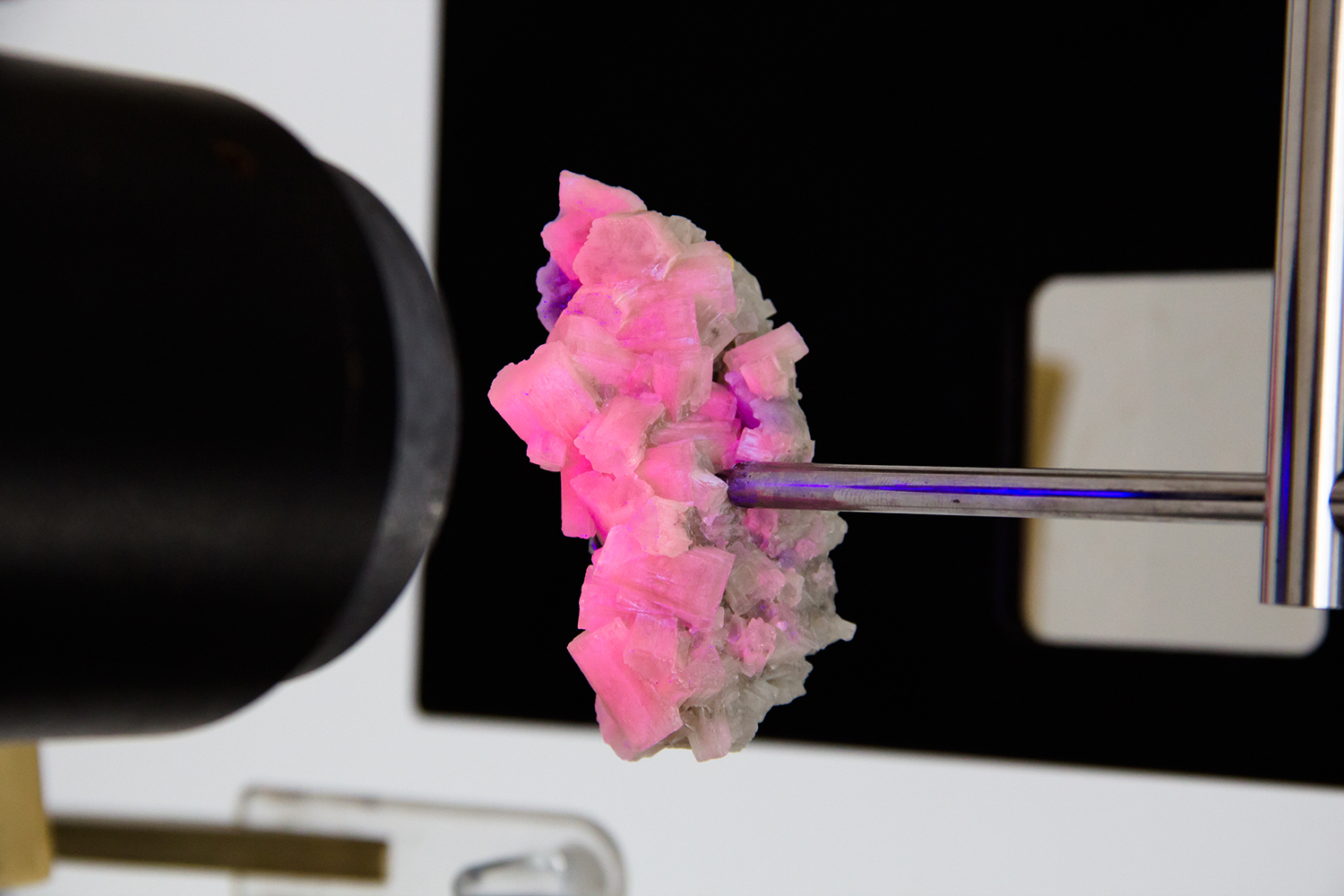

The works realized were built using materials of different types: medical instruments, archive photographs, and natural elements with special properties. The latter were constituted by so-called ‘fluorites’, minerals of different shapes and with different characteristics. Some of these stones if exposed to an (in)visible 360 nm frequency exhibit the fluorescence phenomenon, which takes its name from this substance, changing into various incredible shades.

Some popular beliefs attribute curative powers to fluorite for the memory, disorientation, and lack of concentration.

The belief that a stone in the skull caused an imbalance of the soul began in the Late Middle Ages and continued until the Renaissance, and was held above all in Northern Europe.

According to popular superstitions this little rock, which for unknown reasons appeared inside the head of some individuals, caused behavioural deviance, madness, and strangeness. It was considered to be a foreign body, which had to be removed. This ‘extraction’ process, a practice that pre-dated modern surgery, was represented in paintings, engravings, and literary texts until it fell into the category of those strange practices and beliefs that history has isolated and forgotten.

In any case, cranial trephination was not a medieval invention: Hippocrates wrote about it and archaeology has documented testimonies dating back 8,000 years. Prehistoric people performed operations on the skull using a flint scraper and in various parts of the planet, the practice survives today as a propitiatory rite, or more generally as a method that allows the spirits – whether good or evil– to exit the body and mind.

The Stone of Madness project, begun in 2017, proposed the investigation of factors linked to these traditions and beliefs based on testimonies that have been passed down and are still kept in museums or their archives today.

The works realized were built using materials of different types: medical instruments, archive photographs, and natural elements with special properties. The latter were constituted by so-called ‘fluorites’, minerals of different shapes and with different characteristics. Some of these stones if exposed to an (in)visible 360 nm frequency exhibit the fluorescence phenomenon, which takes its name from this substance, changing into various incredible shades.

Some popular beliefs attribute curative powers to fluorite for the memory, disorientation, and lack of concentration.

The belief that a stone in the skull caused an imbalance of the soul began in the Late Middle Ages and continued until the Renaissance, and was held above all in Northern Europe.

According to popular superstitions this little rock, which for unknown reasons appeared inside the head of some individuals, caused behavioural deviance, madness, and strangeness. It was considered to be a foreign body, which had to be removed. This ‘extraction’ process, a practice that pre-dated modern surgery, was represented in paintings, engravings, and literary texts until it fell into the category of those strange practices and beliefs that history has isolated and forgotten.

In any case, cranial trephination was not a medieval invention: Hippocrates wrote about it and archaeology has documented testimonies dating back 8,000 years. Prehistoric people performed operations on the skull using a flint scraper and in various parts of the planet, the practice survives today as a propitiatory rite, or more generally as a method that allows the spirits – whether good or evil– to exit the body and mind.

The Stone of Madness project, begun in 2017, proposed the investigation of factors linked to these traditions and beliefs based on testimonies that have been passed down and are still kept in museums or their archives today.

The works realized were built using materials of different types: medical instruments, archive photographs, and natural elements with special properties. The latter were constituted by so-called ‘fluorites’, minerals of different shapes and with different characteristics. Some of these stones if exposed to an (in)visible 360 nm frequency exhibit the fluorescence phenomenon, which takes its name from this substance, changing into various incredible shades.

Some popular beliefs attribute curative powers to fluorite for the memory, disorientation, and lack of concentration.